I always believed studying contentious topics was important, but I struggled to teach them. Attempts at productive dialogue devolved into unhelpful debates with familiar voices driving conversations. Or, in many cases, students simply reproduced the same surface arguments dominating our airwaves. In our time of political division, the idea of exploring controversial issues can be scary. We may fear hurt feelings, community blowback, or worse. However, today’s youth deserve to study and shape the pivotal dilemmas of the nation they will inherit.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

- Joseph Campbell

This Campbell quote reflects my experience teaching contentious topics. Despite potential dangers, teaching controversial topics holds rich treasures of transformational learning. A PBL framework helped me rethink my approach, and, after years of revising my practice, students and I began to experiment with approaches that unlocked the power of controversial topics. And now, I’d like to share a few of these ideas with you.

Invite Uncertainty

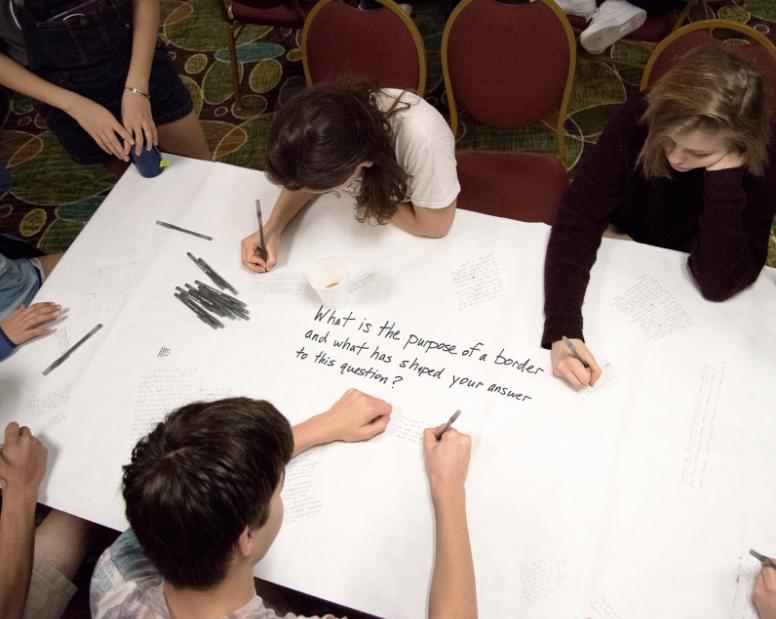

Near the eve of Donald Trump’s first presidential election, I facilitated a project called Border-land. High school senior Daniela Hernandez, artist Jason Reed, and I collaborated with a group of diverse Texas public high school students to explore the question, What is the purpose of a border, and what has shaped your answer to this question? We chose this topic because of increased rhetoric about immigration and the sharp increase in unaccompanied minors crossing the Texas/Mexico border the year prior.

We wanted to gain a deeper understanding of the topic compared to the rhetoric surrounding us. So, we posed the project’s driving question to attorneys, politicians, asylum seekers, Border Patrol Agents, business owners, ecologists, family members, and many more people who had intimate knowledge of the topic. We asked the same question to ourselves as we listened to classmates and read historical documents while standing at a quiet riverbank on the Rio Grande. At the end of each learning experience, students guided the project by considering What additional perspectives should we explore to deepen, expand, or complicate our answer to this question?

Throughout the project, we better saw how every perspective is filtered through lived experience and positionality. We became less invested in “choosing a side” and more intrigued by pursuing nuanced learning and compassionate action. Beautiful work emerged with students exhibiting artwork, engaging in dialogue with global ambassadors, and supporting families released from immigration detention centers.

Border-land was distinct from many other projects I taught. I often felt compelled to rush students towards a broad set of predetermined outcomes, but in Border-land we embraced uncertainty, which I believe was at the core of Border-land’s success. By carving out new spaces for uncertainty, the project enabled a student who believed in tighter border security to joyfully play with a Honduran child while the child’s mother spoke with immigration lawyers, and this same framing allowed a student who despised the Border Patrol to listen intently to an agent’s perspective, learning more about the systems and beliefs guiding his actions.

Begin With a Question To Open Hearts and Minds

Many parts of our personal identities are now intricately intertwined with politics. Ezra Klein writes that today’s parties are more “sharply split across racial, religious, geographic, cultural, and psychological lines. There are many, many powerful identities lurking in that list, and they are fusing together, stacking atop one another, so a conflict or threat that activates one activates all.” The increased layering of our identities upon singular political narratives makes it challenging to teach politicized issues. In today’s schools, just considering a topic’s complexity may threaten to unravel a learner’s personal identity.

To meet this challenge, we must build our collective capacity to open our hearts and minds to nuanced understandings. In PBL classrooms, this begins with forming an effective driving question. Jonathan Zimmerman and Emily Roberson, the authors of The Case for Contention, suggest it's helpful to focus on a “maximally contentious” topic where there is “disagreement among fairly knowledgeable persons about an issue of public concern and the disputants are emotionally invested in the problem.” In other words, a question like Is climate change real? would be ineffective since there is already expert consensus on the topic.

It’s possible that a “maximally contentious” question could be something like Should immigration reform prioritize a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants or stronger border security measures? However, while a question like this can spark spirited debate, it ultimately may encourage learners to think about a topic in a binary–either/or—way. This type of thinking can further entrench learners into the relatively static and simplistic beliefs that neatly dovetail into a politicized identity. Thus, it may help to develop a “maximally contentious” question like What is the purpose of a border? Non-dualistic questions like this can help begin to disentangle an issue’s complexity from the more rigid and surface-level understandings many of us carry in polarizing times.

Even if teachers require students to argue “the other side” of a binary question, learners may finish a project with an enduring understanding that complex problems are two sided, thus diminishing opportunities for imaginative problem solving. More fundamental questions, on the other hand, can encourage learners to challenge core assumptions. For instance, in a project on prison reform, while it may generate heated debate to ask Do prisons perpetuate systemic inequality by prioritizing profit?, a more philosophical question like What does criminal justice really mean? can help students dream of broader possibilities.

Embrace Abstract and Essential Questions

It’s tempting to focus on action-oriented driving questions like How can we reduce the use of fossil fuels in our community? A focus on action can engage students and build advocacy skills. It can even seem unjust to remove the focus from action when many of these topics directly affect student lives.

However, when exploring an issue that’s intensely controversial in a community, I’ve found it’s more effective to uplift deep inquiry above all else. Perhaps this is because so many of us function within wider systems that celebrate arriving at swift and concrete conclusions.

In such environments, the simple act of engaging in compassionate contemplation, courageous listening, and radical uncertainty is in itself disruptive. Thus, in some cases it can be more transformational to pursue fundamental questions like What factors influence how we view natural resources? Questions like this, when marginalized and underrepresented perspectives are foregrounded, can encourage learners to unpack underlying assumptions AND support powerful student advocacy.

Normalize Intellectual Growth

In a project’s driving question about a contentious topic, I always add the phrase, and what has shaped your answer to this question? This small addition normalizes the fact that everyone arrives at different understandings due to their unique experience and positionality. It also illuminates that it’s okay and expected to change opinions based on encountering new information. This normalization of intellectual growth may seem like a simple addition, but it’s a game changer when teaching controversial topics.

For instance, in Border-land we constantly returned to our driving question: What is the purpose of a border, and what has shaped your answer to this question? Students discussed the question in small group dialogue circles, silent chalk talks, and other activities focused on equitable sharing. These practices supported learners in routinely encountering different and emerging viewpoints. Students also reflected on their growth by maintaining a series of portfolio reflections that allowed them to see how and why their answers to the driving question became more nuanced throughout the project.

Additional samples of binary and action-oriented questions redesigned to open hearts and minds:

Original | Redesign* |

How can we stamp out hate speech in our community? | What does “freedom of expression” really mean? |

Should governments have the right to implement mass surveillance programs to ensure national security? | How does surveillance affect our lives? |

How can we improve our state’s educational policy? | What is the purpose of school? |

*Each of these redesigned questions would be followed by the phrase “and what has shaped your answer to this question?”

Center Student Voice and Knowledge

While controversial topics serve as portals for deeper learning, they are also tenuous endeavors. The quickest way to lose the magic of these projects occurs when educators try to lead youth toward their own foregone conclusions on a complex topic. Instead, the best learning happens when teachers center their own uncertainty and curiosity as they engage in courageous vulnerability with the young people they are learning alongside.

This all begins with knowing students well and foregrounding their interests, voices, and strengths throughout the project. Personally, approaching contentious topics in this way has not only enriched my classroom teaching, but my life as well. By pursuing genuinely complex questions alongside students, I’ve more fully witnessed young people’s incredible wisdom, curiosity, and capacity for compassionate creation. These experiences have helped me unpack my own limiting assumptions, opening my heart and mind to a more dynamic and hopeful world.

Explore more ideas!

An effective driving question is a helpful starting point when teaching controversial topics, but it’s just one of many aspects needed to support productive learning. If you would like to explore more ideas, I invite you to read my recent book Teaching Contentious Topics in a Divided Nation: A Memoir and Primer for Pedagogical Transformation. The book contains student reflections along with practical classroom activities and discusses topics like how to build a trauma-sensitive foundation, leverage art as a tool for inquiry, assess for liberation, and foster productive dialogue.

An effective driving question is a helpful starting point when teaching controversial topics, but it’s just one of many aspects needed to support productive learning. If you would like to explore more ideas, I invite you to read my recent book Teaching Contentious Topics in a Divided Nation: A Memoir and Primer for Pedagogical Transformation. The book contains student reflections along with practical classroom activities and discusses topics like how to build a trauma-sensitive foundation, leverage art as a tool for inquiry, assess for liberation, and foster productive dialogue.