As we educators know, calibrating students’ individual academic success is tricky. The more we explore the concept of student-centered learning, the more we realize that students must drive their learning throughout their academic journeys.

Project Based Learning provides the platform to design opportunities for students to spur their learning. However, some of our students come to us with “pebbles in their shoes,” so to speak. This often manifests in dispositions that slow students down and keep them from tackling real world work, no matter how interesting the topic is or how willing they are to do the work.

A 2019 Gallup survey revealed that 52% of teachers believe that their students' projects can be used in the real world. In contrast, only 26% of the students agreed*. This dichotomy underlines that the issue may not lie with students' lack of motivation or interest, but rather with the lack of cognitive connection with strategies to manage real world experiences.

A well-designed project allows students to role play in the adult world from a guided and safe distance. While each project affects students’ depth of knowledge in unique ways, all students might not grasp the social and emotional skills needed to take full advantage of the learning opportunities that PBL provides. For this reason, some teachers have difficulty loosening the reins and extending learning autonomy to their students.

The fear of “losing control” drives many PBL teachers to draft projects where they make the majority of the meaningful decisions throughout the project. Thus they inadvertently diminish the impact of the project design and the relevance of the PBL student experience.

Failing to recognize social and emotional learning gaps in our students has consequences. A student's lack of self-management or responsible decision-making skills, for example, may be perceived as either a personal character flaw or a maturity problem, rather than a lack of “how to” knowledge issue. These issues can be taught and practiced within the PBL learning experience.

Introducing Social Emotional Learning

According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), “social and emotional learning (SEL) as an integral part of education and human development.” CASEL defines Social Emotional Learning (SEL) as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions.”

Transformative SEL in the classroom centers on renorming inequitable settings and systems. Students are encouraged to build strong relationships that facilitate co-learning, and examine the root causes of inequity with the aim of developing collaborative solutions to level the social playing field.

At first glance, the standards-driven teaching paradigm seems to narrow the perimeters in which to learn about or practice SEL competencies. However, we argue that teaching essential SEL competencies should not be left at the periphery, but rather be the “final product" of PBL. In other words, the development of SEL skills is not only an essential partner to PBL, but the end goal. Of course, students enter our classrooms with a broad level of SEL developed skills. Therefore, these competencies need to be taught explicitly with ample opportunities to practice them in meaningful ways within the PBL context.

Developing the Inner Leader

PBLWorks National Faculty member Dr. Matinga Ragatz taught SEL skills within projects in her high school Global Studies classes. Apollo** was a mid-year transfer student who developed a reputation of being “difficult” within weeks of his arrival to the school. He presented the “troublemaker” persona in an obvious effort to hide his true self and keep people at bay. A quick review of Apollo’s schooling history confirmed that he had transferred schools eight times in 10 years, and had cycled through academic suspensions and expulsions due to behavioral issues.

On his first day in Dr. Ragatz's class, he voluntarily sat in the very front of the room, put on a set of headphones, and cranked up the volume on his music. This sent definite and audible signals to his peers that he did not care to be there, and presented an open challenge to anyone witnessing this behavior.

Dr. Ragatz declined his challenge. Since Apollo could not hear her through his music, Dr. Ragatz simply instructed the rest of the class to give him the time and space he needed, and to carry on with their work. After all, the noise emanating from his earphones was barely louder than the aging heating system under the floor vents.

Due to the PBL culture in Dr. Ragatz's classroom, she seldomly conducted class lecturing from the front of the room. Instead, students worked in groups. This made Apollo’s attempt to disrupt the class minimal. During that first week, he continued to try multiple subtle tactics to disrupt the class. However, none produced Apollo’s desired outcome.

Doing an Identity Inventory

Meanwhile, Dr. Ragatz introduced her class’ next project. She reviewed self-awareness and self-management skills lessons as an introduction to the social-emotional learning competencies students would need in their upcoming academic work. The challenge of the project centered around civic engagement. This required students to study, analyze, and design ways to increase citizens’ (their peers) participation in social and civic activities in the community (their school).

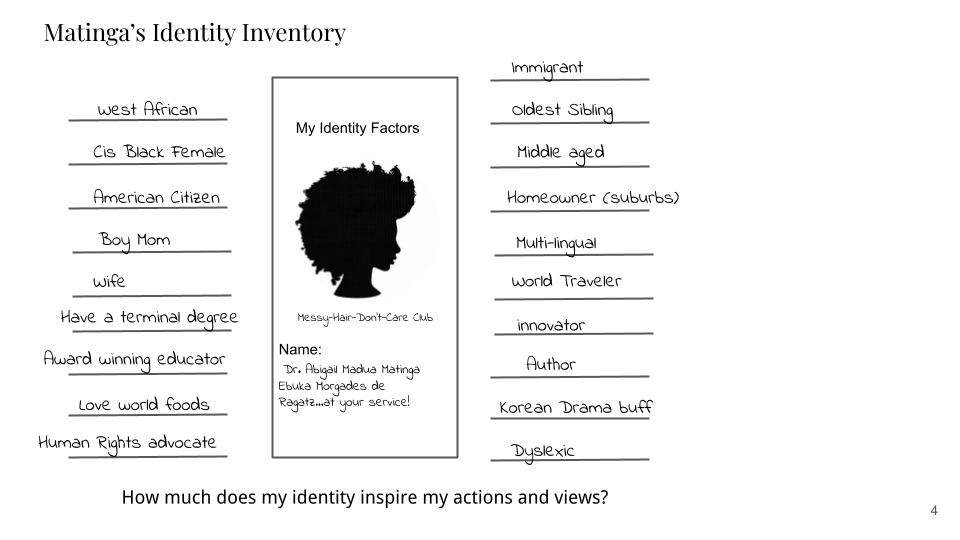

To refresh the notions of self-awareness, students took part in an identity inventory experience. Each student made a list of the characteristics that represented how they perceived themselves. They explored and recorded both visible and hidden aspects of perceived identity. Next, students considered which attributes most shaped their worldviews.

After completing this personal reflection, students shared the most important factors or descriptors that shaped their worldviews about their backstory in triads. For example, one of the students included her role as the oldest sibling in her identity inventory. In later discussions with students that were also oldest siblings, she realized that their world views and many of the ways she showed up in the world coincided—adventurous but responsible, protective, pressured to be good role models, etc.

Despite his resistance early in the class, Apollo gladly delved into his backstory of how events, people, and places had shaped his understanding of his self-perception, and of how others treated him throughout his young life. After all, some of the more eyebrow-raising parts of his personal journey met his need to provide a bit of shock value. Through this exercise, and for the first time in his life, Apollo formed crucial connections that validated the need for his disruptive behavior.

The class was explicitly presented with strategies to manage triggers and make productive decisions when confronted with uncomfortable or stressful situations. This prompted Apollo to reconsider and verbalize how his off-hand comments and manipulative actions affected his relationships with his peers, teachers, and other authorities.

Proactively Teaching Coping Skills

When Apollo and his project mates became disillusioned and rudderless after a failed first attempt at a marketing campaign, Dr. Ragatz taught them how to use tools to help move the project forward. For example, The KARE (Knowledge Gap, Authenticity Gap, Resource Gap, and Effort Gap) Gap guide helped Apollo learn how to circumvent issues that often frustrated the progress of students' projects. This helped him understand new ways to unpack and diagnose problems. It also demonstrated how to navigate stressors to make more productive decisions. This exercise unveiled his leadership abilities and a strong commitment to social causes.

To increase civic and social engagement in their school, students planned and hosted an alternative prom night they called “RAVE for a Cause.” It was well received by the high school students who opted out of the traditional high school prom event.

Apollo participated by raising awareness, advocating for the controversial title and theme of the event, selling tickets, and ensuring it was a positive night for all. His newfound leadership, passion for social causes, and ability to resolve conflicts made him the fulcrum and key to a successful class project. During the project debrief, Apollo reported finding safety in the conversation about identity as an avenue. He was able to reflect on how his backstory affected his perceptions, and learned better coping mechanisms through explicit SEL instruction and practice within the project.

Projects like Community Voices, found in the PBLWorks library, provide teachers with an opportunity to engage the students through key standards and learning goals. It also provides a space where students can learn the incalculable value of these five social and emotional learning competencies. Through this project, students are able to present compelling stories about their own communities’ issues by gathering data to inspire others to take action.

Apollo’s story shows that teaching coping skills to support social emotional learning competencies is imperative in the post COVID-19 classroom. It is no longer sustainable to ignore the importance of teaching social emotional competencies. Educators must intentionally and explicitly teach these skills to equitably support students’ first look into their potential roles in the adult world. PBL is an academic framework ripe for students to develop and practice SEL skills which is, after all, the final product in Project Based Learning.

*Brenneman, R. (2019, February 20). Gallup Student Poll Finds Engagement in School Dropping by Grade Level.

**name has been changed for privacy