Imagine you are in a department meeting planning your next project.

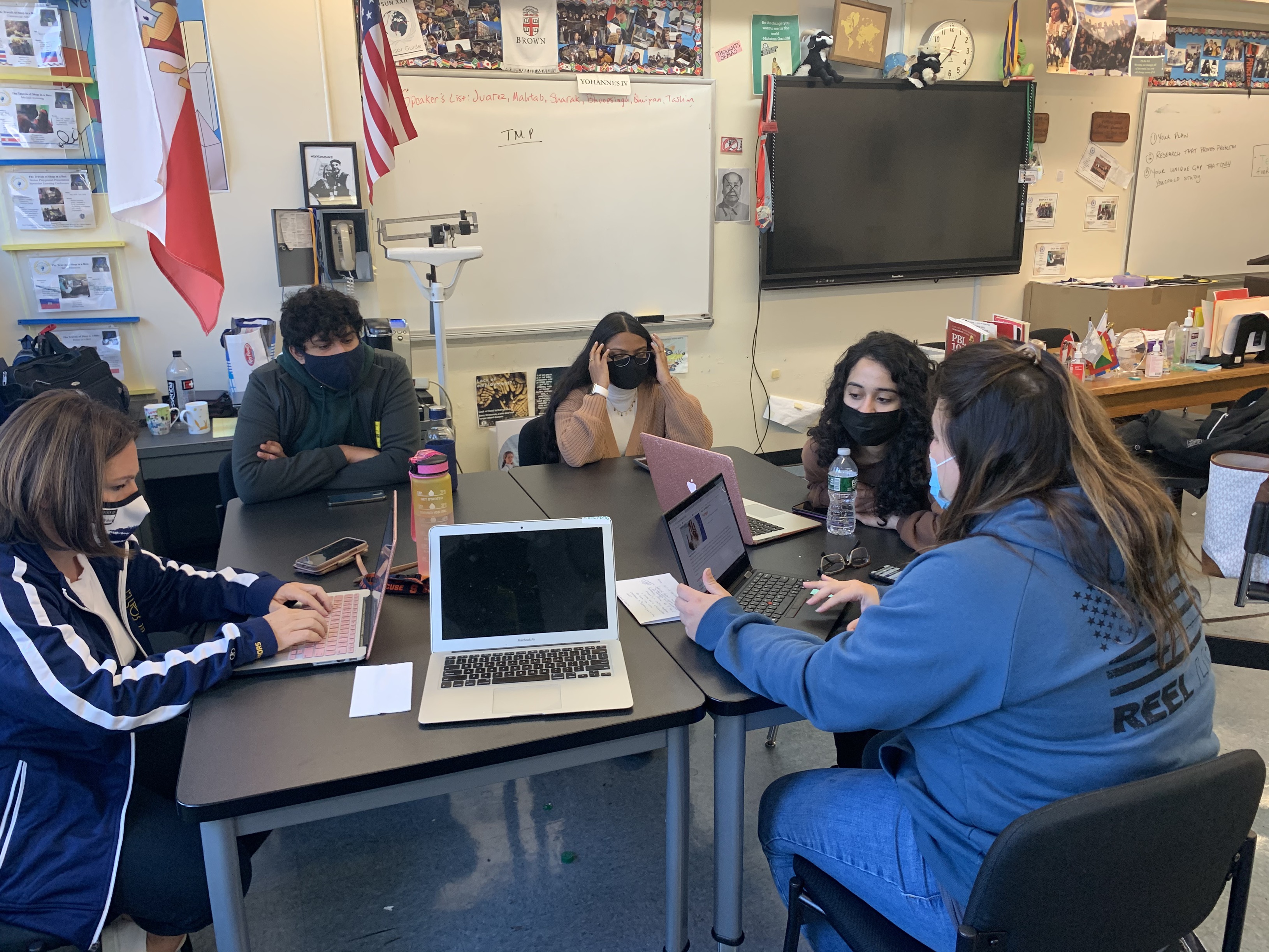

At the table with you are two co-teachers and next to them are two students. As you share your ideas for a project you’re designing, the students are the first ones to chime in with feedback. They comment on the aspects of the project that they think will be engaging and provide specific critique on portions they feel could be improved in order to generate better learning outcomes. You and your colleagues listen to this feedback intently, and adjust the design of the project according to the feedback given by the students.

Later that week when you launch the project, the same two students help facilitate. In fact, these students work with you every day during the project as co-teachers of the class. They work with small groups of students, providing them feedback and support as you do the same, and are just as invested in the success of the project as you are.

If this situation sounds too far-fetched, you don’t teach at Thomas Edison CTE High School in Jamaica, New York. For the better part of a decade, students in Philip Baker and Danielle Ragavanis’ classroom have engaged in project work as both learners and teachers, and in the process they have taken the concept of PBL culture to an entirely new level.

This shared leadership model began as a response to student frustrations about how social justice was integrated into their regular social studies classrooms. Tired of just discussing the problems, students asked to be allowed to explore and create solutions. They wanted a voice in not just how the class was run, but the way they demonstrated their understanding as well.

Despite skepticism among staff regarding the ability of students to manage their own learning effectively, both Baker and Ragavanis agreed to the idea. Before long the students had established their own classroom “charter” that outlined a learner-centered structure and found their own project: helping an all-girls school in Pakistan address fluctuating power disruptions by building the school solar panels. Baker described observing students during that project as sparks flew and his classroom filled with the smell of burning metal. Recalling how independently students were working, he said, “it taught me an important lesson; if you are willing to step back, students will produce amazing things.”

Seeing the benefits of student leadership, Baker and Ragavanis expanded the idea as students asked to be included more in daily instruction. Students became co-teachers, giving feedback on what instruction was needed, a process that led to more effective teaching as well as opportunities for peer support. Baker and Ragavanis saw their own practice improve at the same time they saw student participation increase, especially among those who had previously refused to participate or had a history of behavioral issues.

By the third year, Baker and Ragavanis knew they were really on to something, especially when their colleagues began coming by and asking them what it was they were doing and how they too could adopt the model.

You can imagine the results of this approach to PBL at the school. Students who were once in danger of dropping out were reengaged, and in some cases returned to classrooms they were once thrown out of as co-teachers. The project-based approach used by Baker and Ragavanis resulted in 80% of their enrolled students, including those with IEP’s, passing their AP World History exam. Those students who choose to continue their education at college report back on being more prepared for the rigors of higher education and are better at independent research, writing, and project management. In fact, some report college to be a “let down” because it doesn’t provide them the challenges or structures they were accustomed to at Thomas Edison.

How can other teachers build a classroom culture that supports this level of project work?

Baker and Ragavanis offer these five ideas:

It Begins with Relationships

Build trust and buy-in early on. Start with small things, such as greeting students by name and expecting a handshake as they enter the room. It will pay off in greater participation later. Show students that you are willing to do what you’re asking of them by creating your own exemplars of a project’s products.. Don’t be afraid to share your own interests with your students, such as soccer or debating which bear or actor is “the best”, as students will inevitably respond by sharing theirs, which can then be included in future projects and lessons.

Teach Through Modeling

Students don’t just come into a classroom ready to be leaders or ready to give expert-level feedback. They need to be taught how through modeling. Allow them to practice giving you feedback before they do it with their peers. Have them observe their classmates who are in leadership roles so they can see what it looks like before they are asked to do the same.

Set Expectations High and Keep Them There

Make sure this kind of learning will be hard, but make sure students know that it’s OK to struggle.. If their performance doesn’t meet your expectations, work with them to figure out what didn’t work and make a plan to address it. Your classroom should be one of continuous improvement rather than one where low-quality work is acceptable.

If You Want It To Be Their Classroom, Let Them Make It Theirs

Allow students to construct and adopt their own norms while keeping “teacher powers” you need. Perhaps they can create their own class charter with clearly defined power sharing structures (an important equity lever) while you reserve “veto” power for yourself. Allow them to “nest” through decorations that communicate they are important. (Baker and Ragavanis have pictures of their former students all over the walls, providing a subtle reminder to all current students that they do, and will, always matter)

Be Sure You’re Committed To The Full Journey

Any school taking this on needs to understand that once students have been empowered as leaders and have gained a voice, they will use it. While many of the teachers and administrators were on board with the idea of student leadership, not all were prepared for a student body that expected, or in some cases demanded agency. For example, Thomas Edison’s principal, Moses Ojeda, convened a student input committee and listened while students voiced their frustrations with the disconnect between the hands-on nature of their CTE classes and the traditional format of their academics. Rather than disregard or dismiss these concerns, Ojeda used them constructively to help guide future professional development decisions that would lead to more authentic and experiential teaching in all classes.