Part of the beauty of the human experience is how people communicate with one another. Everyone has quirks in their choice of words, intonation, and nonverbal expression. Language is a form of expression that helps humans weave together and make sense of their personal identities, heritages, spirituality, and unique stories. For example, Native Hawaiians talk story as a means of passing on cultural values, history, and life lessons. Both consciously and unconsciously, humans change the way they communicate depending on who they are speaking with. Code-switching is when someone switches between language choices depending on who they are speaking with. Sometimes code-switching is done as a form of protection against bias from a dominant group. For example, Black Americans will code-switch to sound “more White” in order to try and reduce the possibility of race-based discrimination.

There are over 7,000 spoken languages worldwide that play an active role in preserving culture, identity, and values. In the United States, there are over five million multilingual students in the school system, making them one of the fastest growing student populations. Unfortunately, there are persistent opportunity gaps in math education for multilingual learners. Multilingual learners perform roughly 25% lower on math assessments than their peers, which should come as no surprise since 70% of teachers do not feel prepared to teach multilingual learners, and 80% of teachers do not feel their materials include appropriate supports.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics' (NCTM) Principles to Actions outlines how mathematics education must move from “pockets of excellence” to “systemic excellence” for all students, in particular by addressing inequalities experienced by “traditionally underrepresented groups,” which include Black and Brown students, multilingual learners, and their intersection. TODOS asserts that in order to help multilingual learners thrive in mathematics, we must acknowledge that:

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics' (NCTM) Principles to Actions outlines how mathematics education must move from “pockets of excellence” to “systemic excellence” for all students, in particular by addressing inequalities experienced by “traditionally underrepresented groups,” which include Black and Brown students, multilingual learners, and their intersection. TODOS asserts that in order to help multilingual learners thrive in mathematics, we must acknowledge that:

- The use of students’ first language is a human right and should be promoted in the mathematics classroom.

- Young students should practice receiving feedback from both each other and from trusted, familiar adults. Ever find yourself wondering how to manage the role of feedback in PBL with three-, four-, or five-year-olds? Why not involve families? How beautiful might it be to invite a few caregivers in to serve as participants during feedback rounds? Or perhaps as partners for reflection to help small groups of students think through what they are learning and how their learning has changed based on feedback from peers?

- Multilingual learners should be viewed as students who possess knowledge, strengths, and resources.

- Every mathematics teacher is a language teacher—'particularly the academic language used to formulate and communicate mathematics learning.

Though these principles can feel daunting to take on as an educator, there are practical ways to begin implementing them in the classroom to help create a language-inclusive environment where students of all linguistic backgrounds can engage in rich mathematical discourse.

Language, Culture, and the Math Classroom

Educators are often unaware of how they promote or discourage students’ use of different languages, dialects, and preferred communication styles in their classrooms. Most curricular resources are only in English and are written in a specific academic style of English that favors the language of the White middle class. Teachers may also unconsciously control students’ expression in the way they signal how it sounds to be scholarly in their classroom.

For example, disciplining students for interrupting, disagreeing, or speaking too loudly or quietly sends the message that those ways of communicating are not “scholarly.” Students are brilliant when it comes to recognizing patterns and observing their teachers’ actions and words to make inferences about their beliefs.

At worst, this leads students with communication styles and language choices outside of the dominant group to dis-identify as doers of math. It also sends the message that to be successful in learning mathematics, they must leave part of their means of self-expression, and therefore their cultural identity, at the door.

If teachers do not take an active stance to share power and promote translanguaging, the classroom can become a place in which erasure of culture and language is done at scale to entire generations of students. It is particularly harmful to Black and Brown students to restrict the ways in which they communicate academically. When colloquial and home languages are not deemed to be important or connected to the school subjects they are learning, students are receiving the message that, for example, they can’t fully be Black and a mathematician.

Teachers' Attitudes Towards Language Development in Math

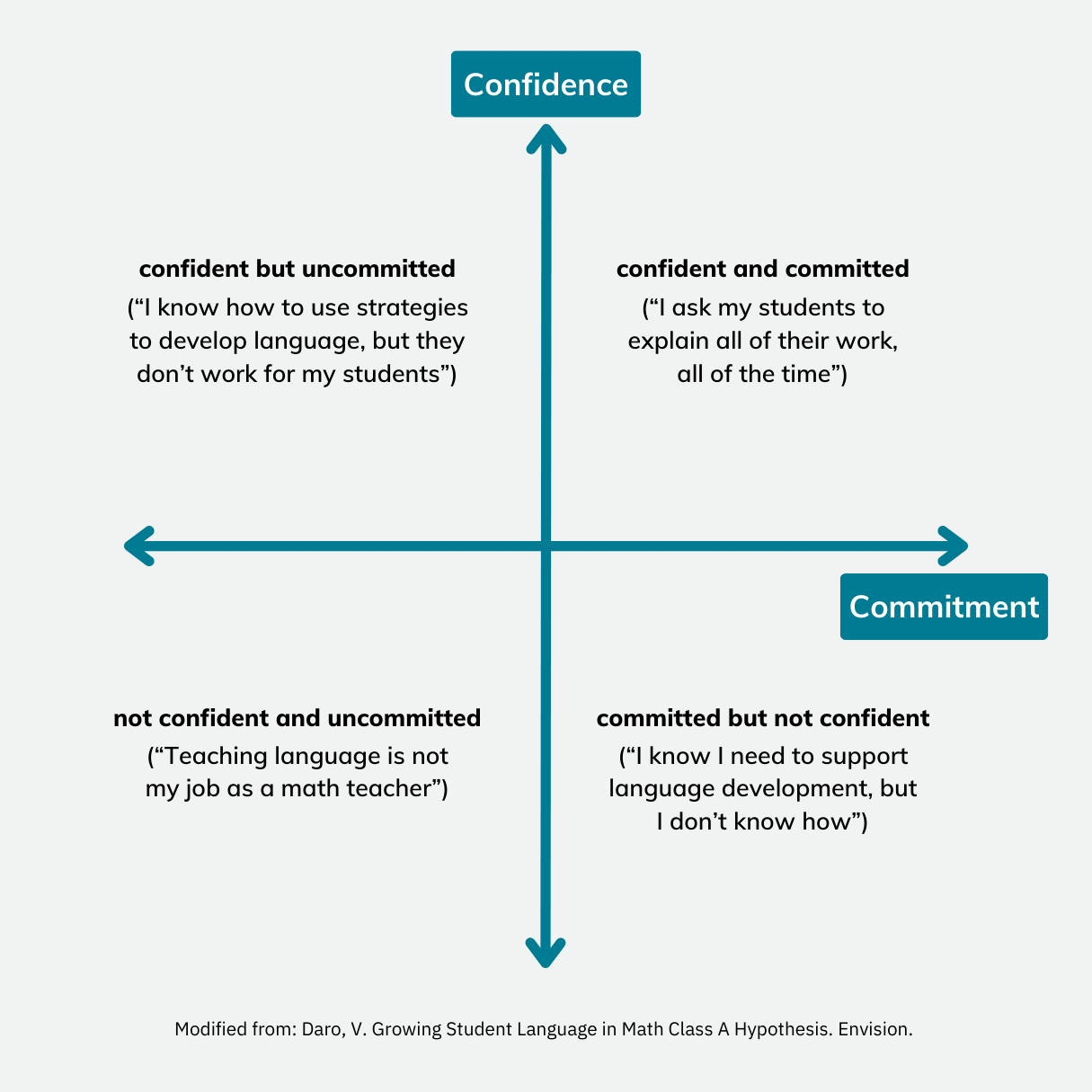

All teachers, including math teachers, are responsible for developing students' literacy in both English and students’ home languages through their discipline. For some math teachers, this can feel overwhelming, outside of their expertise, or like an add-on to math instruction. Dr. Vinci Daro developed a framing of math teachers’ common sentiments towards supporting language development, seen below.

Though designed to interrogate math teachers’ sentiments toward general language development, this can also be useful framing to interrogate common sentiments toward supporting the development of home languages. With just 13% of teachers being bilingual, there is a known challenge for monolingual teachers in particular to incorporate students’ home languages as assets within instruction. The challenge exists for bilingual teachers as well; Dr. Jose Medina refers to his own prior teaching experiences as having been conditioned to be a linguistic oppressor. In many ways, teachers have been trained to "fix" students’ language through the promotion of monolingual, monocultural communication. Dr. Medina asserts that teachers must break the cycle in their classrooms, which can be done by empowering students to see connections between their cultural identities and the content they are learning.

Language and Culture in Project Based Mathematics

In the academic context, translanguaging recognizes the fluidity of communicating in multiple languages, such as Spanish and English. Rather than the idea of an off-on switch to go between languages, translanguaging recognizes the full linguistic repertoire of learners and encourages them to make sense of new ideas using their proficiencies across languages. Translanguaging also encourages sense-making using students’ colloquial languages. For example, students can decode academic language with respect to their fluency in AAVE. All students can benefit from a classroom welcoming of translanguaging because academic English is rarely the common spoken language in any household.

Translanguaging is not only beneficial for multilingual learners, but monolingual students as well. It is a means to help students decode and practice using academic English while making connections to conversational English (and other languages) spoken outside of the classroom. One such way to incorporate students’ linguistic brilliance in the classroom is through co-crafted, multilingual word walls. Having students contribute their own words, phrases, and definitions to the class word wall helps students make connections to the mathematics that they may not have made alone. For example, the mathematical definition of constraints can be inferred from the Spanish translation limites, which contains limit. In Greek, the word for zero is μηδέν (pronounced: midén), meaning literally, “not even one”. Learning about zero through multiple linguistic lenses sheds light on its meaning and gives students multiple ways to make sense of the concept.

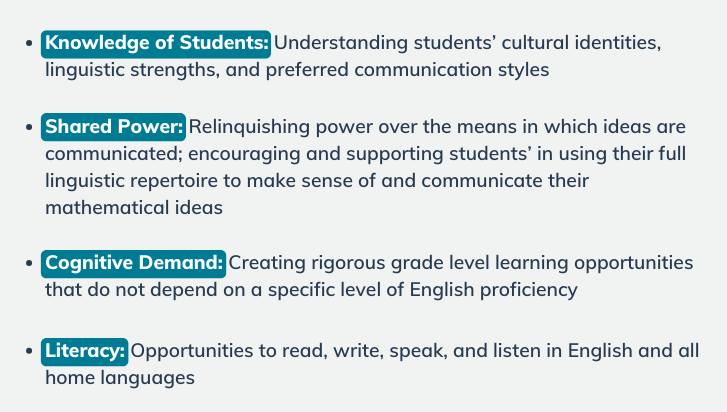

Creating a translanguaging-inclusive math classroom aligns to the PBL Equity Levers in the following ways:

In addition to the translanguaging, it is important to honor student’s identities through their preferred communication styles. Teachers can promote Shared Power by providing opportunities for students to communicate authentically during learning activities. If students feel they must code-switch during learning activities, they may be hindered from making connections to new or prior knowledge simply because they express themselves differently than the dominant group.

It is also essential for teachers to reflect on their classroom management practices and how they may unconsciously discipline students for communicating in certain ways. For example, Black students are disproportionately disciplined for subjective reasons such as “disrespect” and “excessive noise.” With more awareness of personal biases and communication preferences, teachers can create a more inclusive classroom and validate students’ intersectional identities as learners.

Here are some ways you can center students' cultural and linguistic brilliance in math lessons:

If you have… | |

|---|---|

1 minute | Incorporate students’ home languages and colloquialisms (including youth phrases) into the common language of the class and/or language used during instruction. Draw upon words and phrases students use during and after class, making a point to understand the appropriate pronunciation or intonation. |

3 minutes | Facilitate a class culture-building activity where students answer different prompts about their preferred communication styles. For example, Stand up if you:

Take notes or observe students preferences to inform options for communication in future activities. |

5 minutes | Give a written exit ticket, reflection journal, or prompt where students are encouraged to respond in their preferred language. Give example responses to the class as needed to show how different styles of written language can still get at the essence of the prompt/task. |

30 minutes |

|

3 weeks | Teach a unit of study as a project, centering opportunities for students to contribute their cultural and linguistic brilliance. For example, the 6th Grade Project “Community Recipes” in the PBL Teach curriculum has students write recipes for a community member or loved one. Students record recipes that have personal meaning to their loved one and present the recipes in their preferred languages. They also choose a story to tell (in any language) about the recipe, and compile their stories into an online food blog with their team. |

(Note: In linguistically diverse classrooms, it is important to invite students to share their comfort level in their language being centered, borrowed, or adopted by others in the class. When students belong to one or more marginalized groups, it is important to ensure that the adoption of their language is done in ways that make them feel safe and supported.)

Looking to continue the conversation? Reach out to Jillian at: [email protected].