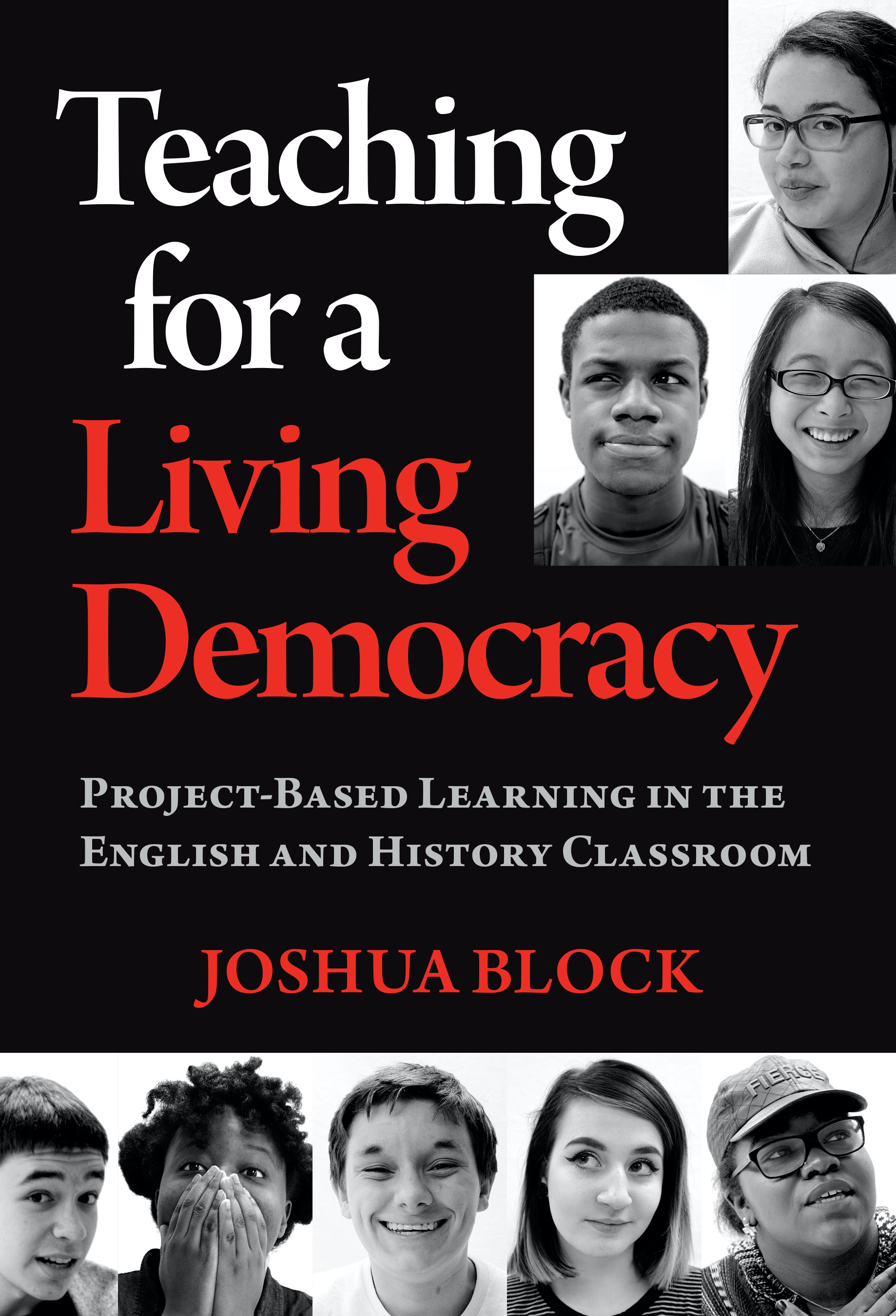

(Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from the book, Teaching for a Living Democracy: Project-Based Learning in the English and History Classroom, from Teachers College Press, 2020, which I highly recommend. It is an especially timely book, given our new reality during the pandemic and our society’s focus on systemic racial oppression.)

I once taught a student who spent months struggling with depression and cutting.

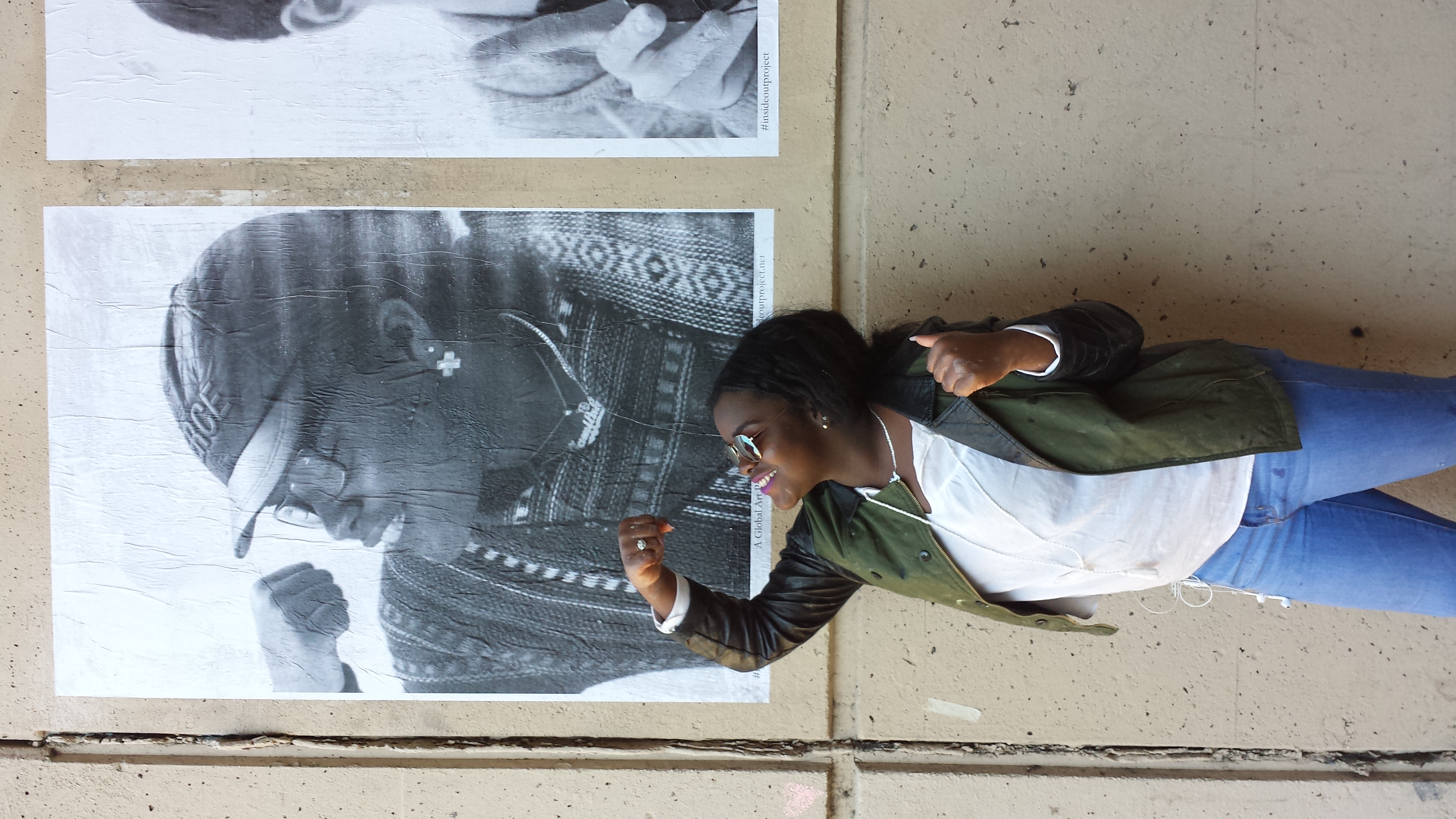

One day, I watched her stand up in front of the class and share a poem that she’d written about facing her struggles. When she finished, the class erupted with cheers and calls of, “You go!” and “That’s right!” The student walked back to her seat attempting to conceal her smile and pride.

In the fall of 2014, after reading Michelle Alexander’s essay Telling My Son About Ferguson (2014) together, I listened as a group of students from different backgrounds, some of whom had memories of traumatic experiences at the hands of police officers and others who had police officers in their families, shared responses to the death of Michael Brown. The room was filled with sadness, fear, and hurt as students disagreed, yelled, and cried but also heard each other. I will never forget what it was like for us all to listen to Joy, speaking to the class with her hand over her face as she began to cry, “I hate this stuff. It makes me really angry! Makes me not want to have kids.”

The other day, a student dragged his feet as he slowly entered my classroom, having made multiple trips during the night between his home and the 24-hour pharmacy. He had been trying to get the medicine for his father’s cancer treatment but had continually run into bureaucratic obstacles symptomatic of a dysfunctional healthcare system.

Years ago, when I spoke to a student whose grades and engagement in class had dropped dramatically during December, I learned that her family’s heat had been cut off. She was unsure when her family would have the money to pay the bill in order to get it turned back on. Another year, I learned that a student had been living without electricity for months. She had become accustomed to doing her homework and putting on her

makeup by flashlight.

I share these examples not because they are exceptional nor for dramatic effect.

Rather, they illustrate some of the different ways that many students in our society come to school with burdens, trauma, and unresolved issues. Celebrating the potential of young people and the power of democratic education means acknowledging and understanding the different ways that our society falls short. Believing in education and in human potential requires acknowledgement of inequalities that are ingrained in the fabric of our society. Being an educator means meeting people where they are and helping them understand themselves, their lived realities, our society, and the world.

In our country, where there is enormous educational inequity, teaching contexts differ drastically. In some teaching contexts, many students may arrive at school not having had their basic needs met. At the other end of the spectrum, many students come from environments steeped in vapid materialism and overconsumption. While educators and activists work for structural change, we can seek to challenge and nurture young people, pushing a range of students to develop their own understandings of social change and possibility.

Unequal schools and the disparate daily realities of students are a reminder that educators must develop pedagogy that speaks to and examines different understandings and experiences. To ignore the lives of young people and current social realities is to fail students and miss the potential for education to inform, challenge, and inspire change. There is work to be done in all classroom settings — exclusive institutions, high- poverty areas, mixed-population schools, and environments not easily summarized. The work differs depending on the community and the individuals.

One pathway for acknowledging and honoring students’ realities is to use aspects of students’ lives as starting points for inquiry.

Years ago two veteran Philly teachers, Marsha Pincus and Dina Portnoy, introduced me to the idea of Language Autobiographies. The project, designed by Marsha and taught by the two master teachers, requires students to see their world and their identities in new ways (Cook-Sather, 2009). With this project as inspiration I designed a unit that requires students to interrogate systems of language, power, and identity while creating work that allows them to uniquely analyze and respond to their life experiences. Part of my intention in sharing this unit is to offer an example of ways that technology can be strategically utilized to deepen the intellectual experiences of learners within the framework of teaching for a living democracy.

To learn more about this project-based unit--and many others--get this powerful and timely book: Teaching for a Living Democracy: Project-Based Learning in the English and History Classroom, from Teachers College Press, 2020.

Follow Joshua Block on Twitter @jhblock and visit his website: https://mrjblock.com/.