My father is a PBL skeptic. With his son (me) spending his days as a PBL workshop facilitator, you might say we perfectly bookend the technology adoption curve—I as the “innovator,” my dad as the “laggard.”

I don’t like that verbiage. One word connotes something positive and edgy, while the other suggests little more than a group with their heads in the sand.

In many workshops I have facilitated, there are often a small group of teachers who would be considered “laggards,” but are what I like to call the “ultra skeptics.”

These are usually (but not always) more experienced or senior teachers who have a well-refined pedagogical approach that works for them, and has always worked for most of their students. They have also been around long enough to see many new initiatives come and go with lots of fanfare but few results.

I welcome and applaud the skeptics.

Being a discerning, critical thinker is important, and a viewpoint that is sorely needed in schools that are quick to change course and track towards the newest, shiniest idea on the education horizon.

However, PBL isn’t just a “new shiny idea.” It is something with real value that should be core to the student experience. For that reason, I am driven to help every teacher, skeptic or otherwise, find their path to PBL.

The layout of this path has recently become much clearer, thanks to a conversation I had with my father.

While we don’t often talk about my work, he will occasionally mention an article or a blog post that he has stumbled across that discusses PBL, and enthusiastically relays his takeaways to me in the form of “Hey, did you know…” or “I’ll bet you’ve never heard that…”

These conversations often end with him saying, “Reading this stuff makes me want to go back to the classroom,” which I always find a little odd. My dad was a laboratory science teacher (among other things), so the idea of “learning by doing” isn’t foreign to him. One day I asked him, “Dad, you’ve read about Gold Standard PBL. Do you think you were a PBL teacher?”

His response was “no,” and included a laundry list of very familiar and very real challenges still being experienced by educators today.

“Education should be like a meal,” he said, “If you enjoy it, you’ll come back for more.” But preparing appealing meals wasn’t always possible for him.

During the prime of his career, education was beginning to shift towards a seemingly endless procession of district, state, and national tests. By the time my father retired, the average graduate in his home state of California would take nearly 120 state-mandated tests during their K-12 career, and the pressure to “teach to the test” pushed aside time for concepts and learning experiences that would have lent themselves to Gold Standard practices.

I was surprised to hear my dad lament about what he wasn’t able to do with his time in the classroom, especially considering his lustrous career. When he retired after several decades of service, he had a long list of accolades that included leadership positions, prestigious awards, and the respect of both his colleagues and his students. And while I am his son and therefore inherently biased, I know that this is true because I witnessed it first-hand while attending the high school where he taught.

Every day of my high school career, I was driven to school by my dad. When you’re chauffeured by the man for four years of your life, you amass a lot of evidence about his skills as a teacher. This repeated exposure showed he wasn’t just a good teacher, he was probably one of the great ones.

Rarely did a week go by where I wasn’t pulled aside in the hallway by an upperclassman who would recognize me, grab me by my collar, and repeat the all too familiar refrain, “Are you Mr. Fester’s son? Dude, your dad is so f___ing cool!” (I went to a public high school, so please excuse the colorful language.)

So, even if my dad wasn’t a PBL practitioner, he was successful, and I wondered if he, like many others, just didn’t quite finish his PBL journey before he exited the classroom. I asked him, “Knowing what you now know, do you think Gold Standard PBL would have been possible under the circumstances you’re describing?”

A pause.

I bit my lip and braced myself for the reply, but much to my delight he replied, “Yes… but I would have needed some things.”

I fumbled around for a piece of paper, knowing that Mr. Fester was once again about to start class. “Ok, great. What could your administration have done to support you in doing what you knew worked best for students?”

Class is in session.

1. Sustained Support from Within

While there is undeniable value in getting teachers access to high-quality professional development and training, more is needed. Consultants come, but they eventually leave, so what happens if you need help the day after they are gone?

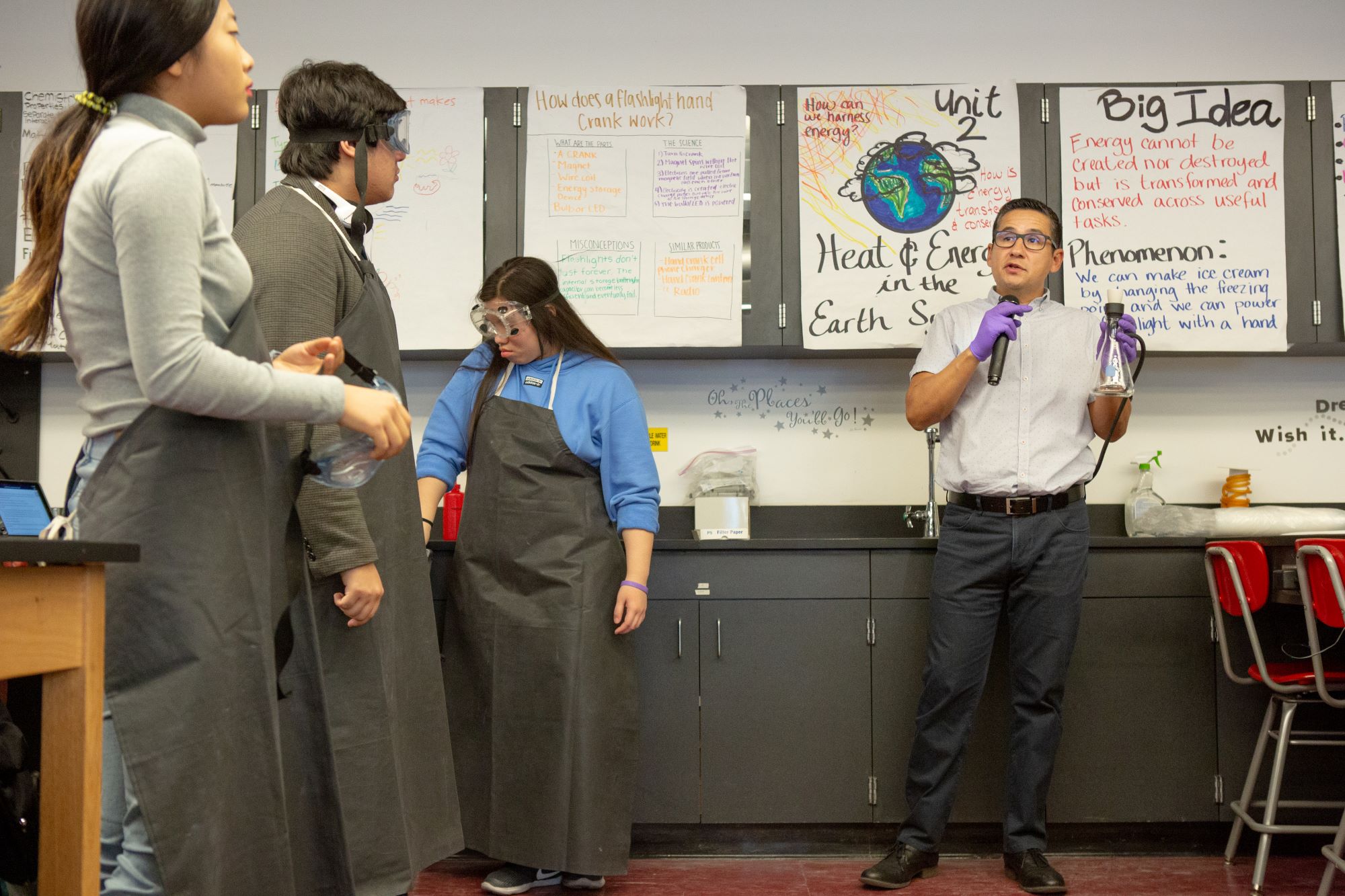

Sustaining PBL requires sustained support, and much of this support can come from within a school. In thinking of his chemistry class, many of the real-world applications of his content required the application of higher-level math that was outside his expertise. Collaborating with a colleague from down the hall would have allowed the development of projects that infused both math and chemistry. Additionally, the professional and personal connections within his faculty might have helped him procure outside experts that could have come in and supported his projects when his colleagues couldn’t.

2. Keep Bringing It Up

Teachers like my dad are wary of “yet another initiative,” and with good reason. Too often, new ideas, projects, or approaches are launched at schools and just as they are getting crucial buy-in and gaining steam, they disappear. Support dries up, but most importantly it isn’t given air time, and without air, it fizzles and goes out.

To prevent this, make sure PBL is given air as often as you can. Dedicate time at faculty meetings to allow teachers to share their success stories. Highlight student project work in public areas of the school. Dedicate space in newsletters, websites, or board meeting minutes so all of your teachers know PBL still matters even after the workshop ends.

3. Encourage Coaching Conversations

One of the key ingredients missing from my father’s school was a thought partner. A person who would be willing to listen, bounce around ideas, and engage in question-based dialog that would give these ideas form via actionable learning sequences and projects.

Many schools have the structures in place to support this already, either in the form of grade-level, department, or PLC (Professional Learning Community) groups. Dedicating time for teachers to help each other develop ideas is crucial for taking a project from the concept stage and moving it into something that creates meaningful and deep learning for students.

If your teachers need help having these kinds of conversations, check out the protocols on the website of the National School Reform Faculty. The protocols found on this site can be adapted for any age classroom or learning environment.

4. Just Do It

PBL is hands-on learning. Encourage teachers to set aside their “yeah, buts,” take the plunge, and launch a project.

If they want to do it as a co-facilitated project with a more experienced colleague, allow that. If they want to design something small, like a two-week endeavor, allow that. If they need help finding an authentic audience for their final products, volunteer to be there and bring a friend.

Listen to their perceived obstacles, empathize, then help them remove them. Once they feel PBL success, they will be that much more likely to do it again and again. That’s how you shift culture.

5. Process the Positives

You’ve probably heard the saying, “'FAIL' stands for ‘First Attempt in Learning,’” but for many educators like my dad, that doesn’t matter. Failure, real or perceived, is enough to take the wind out of the sails of even the most resilient of educators, and kills the buy-in needed to sustain a new endeavor.

My father said, “If I’m doing something, I don’t want to fail. And if I have a bad experience, I’ll probably be done.”

It is all too common for the first project to not meet the expectations of the teacher facilitating them, so make sure to find time for your teachers to process the positives. No project is a total failure, so provide the critical lens they need that helps them find the successes and reassures them that their efforts were not in vain.

Make sure to publish and share highlights from the project, even if it’s just snippets of the project process you’ve captured on your phone. All projects produce some sort of learning, even the “failures,” so find it, and lift it up.

Retired for more than 15 years and he’s still taking me to school. Happy Father’s Day, dad.

If you’re a leader at your school or district and wondering how you can best support the unique PBL journey each of your educators is on, give the list above a go. For even more support, reach out to our district and school services team to explore partnering with our expert PBLWorks team. Who knows, we might even get to meet in person!